|

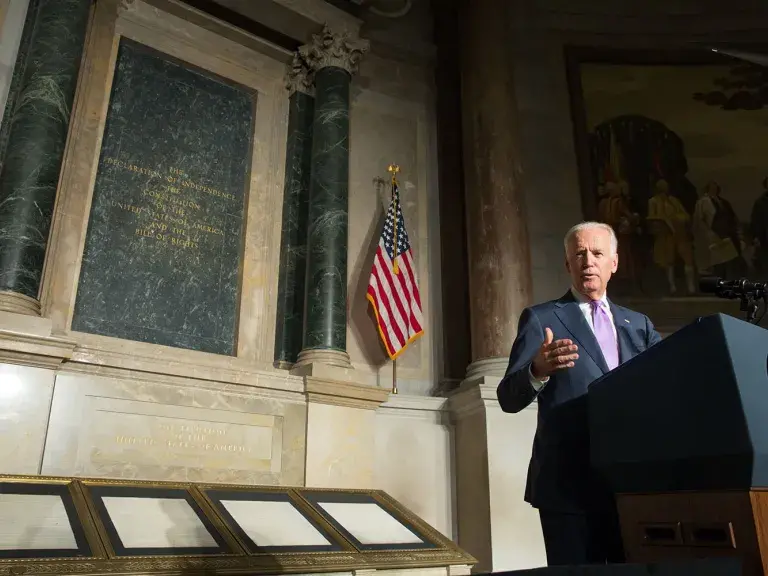

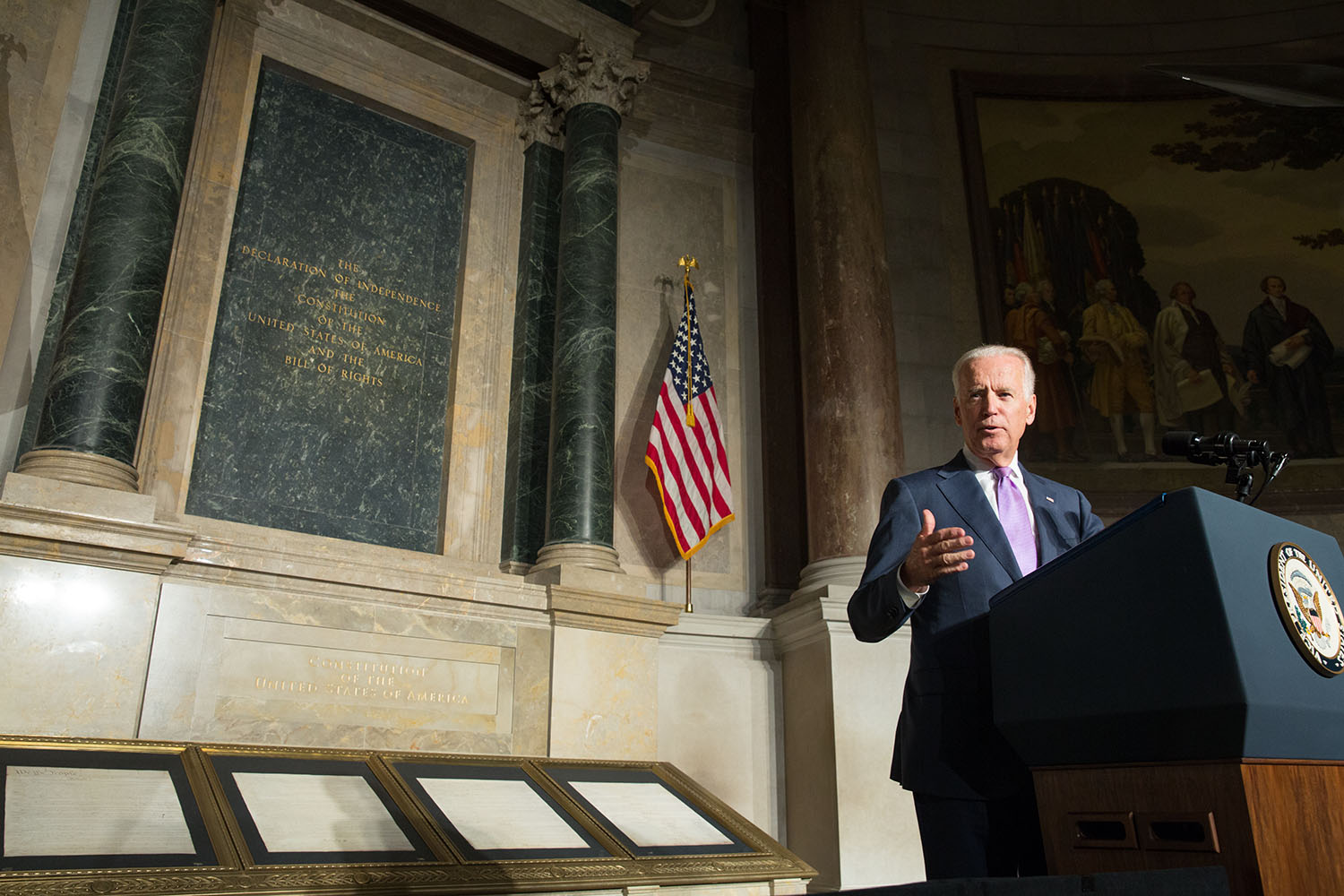

Today, March 15th, President Biden signed the VAWA 2022 Reauthorization into law.[1] “The long awaited reauthorization of VAWA comes at a critical time when American Indian and Alaska Native face unprecedented levels of violence on tribal lands and in Alaska Native villages,” said Jana L. Walker, Senior Attorney at the Indian Law Resource Center and director of its Safe Women, Strong Nations project. “We hope that VAWA 2022 will be a strong step forward in helping to end the epidemic levels of violence against Native women and lead to justice for all victims, including indigenous women who are among the most vulnerable in this country.”

VAWA stands as one of the most critical laws passed by Congress in the last three decades. That is why the lapse of VAWA some three years ago put so many women’s lives in jeopardy, especially those in Alaska where 228 tribal governments — all but one — have been unable to take advantage of the special domestic violence criminal jurisdiction in VAWA 2013 based solely on the way their lands were classified.

“The Indian Law Resource Center has been working diligently both domestically and internationally to restore safety to indigenous women and to protect their most basic human right, the right to live free of violence and discrimination,” said Chris Foley, Senior Attorney at the Indian Law Resource Center.

While some studies have shown domestic violence and sexual assault rates have decreased significantly since VAWA 1994 became effective,[2] sadly, that is not the case for American Indian and Alaska Native women. “Today the federal statistics on violence against American Indian and Alaska Native women show that, if anything, the situation has become much more dire,” noted Foley, “and, on top of that the COVID-19 pandemic has only made a bad situation even worse. That is why the reforms in VAWA 2022 are so urgently needed.”

Findings and Purposes Updated and Clarified

Section 801(a) of Title VIII, Safety for Indian women, of VAWA 2022 explicitly finds that:

- “American Indians and Alaska Natives are . . . 2.5 times as likely to experience violent crimes; and at least 2 times more likely to experience rape or sexual assault crimes”.

- “[M]ore than 4 in 5 American Indian and Alaska Native women have experienced violence in their lifetime”.

- “[T]he vast majority of American Indian and Alaska Native victims of violence — 96 percent of women victims and 89 percent of male victims — have experienced sexual violence by a non-Indian perpetrator at least once in their lifetime”.

- “Tribal prosecutors for Indian Tribes exercising special domestic violence criminal jurisdiction report that the majority of domestic violence cases involve children either as witnesses or victims, and the Department of Justice reports that American Indian and Alaska Native children suffer exposure to violence at one of the highest rates in the United States”.

- “[C]hildhood exposure to violence can have immediate and long-term effects, including increased rates of altered neurological development, poor physical and mental health, poor school performance, substance abuse, and overrepresentation in the juvenile justice system”.

- “[A]cording to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, homicide is — (A) the third leading cause of death among American Indian and Alaska Native women between 10 and 24 years of age; and (B) the fifth leading cause of death for American Indian and Alaska Native women between 25 and 34 years of age”.

- “[I]in some areas of the United States, Native American women are murdered at rates more than 10 times the national average”.

- “[A]ccording to a 2017 report by the Department of Justice, 66 percent of criminal prosecutions for crimes in Indian country that United States Attorneys declined to prosecute involved assault, murder, or sexual assault”.

- “Native Hawaiians experience a disproportionately high rate of human trafficking, with 64 percent of human trafficking victims in the State of Hawai’i identifying as at least part Native Hawaiian.”

These disproportionately high rates of violence against American Indian and Alaska Native women are largely due to an unworkable and discriminatory legal system that severely limits the authority of American Indian and Alaska Native nations to protect indigenous women and girls from violence, and persistently fails to respond adequately and diligently to these acts of violence, allowing the perpetrators to act with impunity. Together these factors create a situation where American Indian and Alaska Native women are denied access to justice and to meaningful remedies, and are less protected from violence than other women because they are indigenous and are assaulted on tribal lands or within Alaska Native villages.

In the last decade, Indian and Alaska Native nations, indigenous women, and their allies have successfully worked for key reforms in United States law that promote the collective rights of self-determination and self-government and indigenous women’s human rights to live free from all forms of discrimination and violence recognized in the UN and American Declarations on the Rights of Indigenous Peoples. VAWA 2013, which restored limited tribal criminal authority over certain non-Indian perpetrators that commit domestic violence, dating violence, or violate protection orders within Indian country and their tribe’s jurisdiction, is but one example of this — and marked one step by the United States toward meeting its obligations under domestic and international law.

Importantly, Section 801(a)(4) of VAWA 2022 acknowledges the success of tribal governments implementing VAWA 2013’s special domestic criminal jurisdiction, noting “that Indian Tribes exercising special domestic violence criminal jurisdiction over non-Indians pursuant to section 204 of Public Law 90–284 (25 U.S.C. 1304) (commonly known as the Indian Civil Rights Act of 1968), restored by section 904 of the Violence Against Women Reauthorization Act of 2013 (Public Law 113–4; 127 Stat. 120), have reported significant success holding violent offenders accountable for crimes of domestic violence, dating violence, and civil protection order violations”. However, as we know, significant barriers and dangerous gaps have remained. Even where some tribes have been exercising the special domestic violence jurisdiction, it is very, very limited. Since VAWA 2013, tribes have still generally lacked authority to prosecute non-Indians who rape, murder, stalk, or traffic American Indian and Alaska Native women. Strangers may still enter reservations or Alaska Native lands and commit violent crimes against Indian and Alaska Native women with impunity.

Strengthening and Expanding the Criminal Jurisdiction of Tribal Authorities over Non-Indians

The Tribal Title of VAWA 2022, set forth in Title VIII, includes Subtitle A, Safety for Indian Women, as a federal response to legal gaps and barriers remaining in VAWA. Subtitle A responds to the epidemic of violence in Indian and Alaska Native communities by reaffirming and restoring Special Tribal Criminal Jurisdiction to participating tribes over non-Indian offenders that commit not just crimes of domestic violence, but now any covered crimes that occur in the Indian country of the participating tribe. Covered crimes include: “(A) assault of Tribal justice personnel; (B) child violence; (C) dating violence; (D) domestic violence; (E) obstruction of justice; (F) sexual violence; (G) sex trafficking; (H) stalking; and (I) a violation of a protection order.” Section 804 further clarifies that this expanded jurisdiction includes the jurisdiction of tribes in Maine.

Alaska Tribal Public Safety Empowerment

Subtitle B, Alaska Tribal Public Safety Empowerment, of Title VIII, is intended to restore safety for Alaska Native women by reaffirming the inherent authority of Alaska tribes over all Indian persons in a village and creating an Alaska pilot program allowing up to 30 Alaska tribes to exercise Special Tribal Criminal Jurisdiction over Covered Crimes committed by non-Indians (unless both the alleged victim and alleged defendant are non-Indians) within a village. The Special Tribal Criminal Jurisdiction of an Alaska tribe is concurrent with any jurisdiction possessed by the State of Alaska or the United States. The Attorney General, in consultation with the Secretary of the Interior, is authorized to select up to five Alaska tribes per year to participate in the pilot program.

Section 811 of Subtitle B includes Congressional findings based on the 2013 report of the Indian Law and Order Commission that Alaska Native women:

- “are overrepresented in the domestic violence victim population by 250 percent;”

- “in the State of Alaska, comprise — (i) 19 percent of the population of the State; but (ii) 47 percent of reported rape victims in the State; and

- “as compared to the populations of other Indian Tribes, suffer the highest rates of domestic and sexual violence”.

Section 811 also reiterates the Indian Law and Order Commission’s 2013 recommendation that “devolving authority to Alaska Native communities is essential for addressing local crime” as “[t]heir governments are best positioned to effectively arrest, prosecute, and punish, and they should have the authority to do so-or to work out voluntary agreements with each other, and with local governments and the State on mutually beneficial terms”. Subtitle B also acknowledges the federal trust responsibility to assist tribes in safeguarding the lives of Indian women.

Other Key Provisions

Additional key reforms in VAWA 2022 include, but are not limited to, making permanent the Bureau of Prisons Tribal Prisoner Program that allows tribal nations to place offenders, sentenced in Tribal Court to one year or more, in federal facilities; amending the Tribal Access Program to ensure that all tribal nations can access the national crime information systems for criminal and non-criminal justice purposes; and ensuring non-Indian defendants must exhaust all tribal court remedies before appealing to a federal court.

The reauthorization of VAWA 2022 extends the law through 2027.

A VAWA 2022 Senate Section by Section Summary is available at https://www.murkowski.senate.gov/imo/media/doc/2.9.22%20VAWA%20Senate%202022%20Section%20by%20Section.pdf.

* * * * * *

We extend our thanks as well to all of the members of Congress who voted in favor of VAWA 2022 and stronger more just tribal provisions aimed at strengthening the inherent criminal authority of Indian and Alaska Native nations and improving the safety for all American Indian and Alaska Native women regardless of whether they are assaulted on tribal lands or within an Alaska Native village.

[1] The VAWA 2022 Reauthorization is included within H.R. 2471, the Consolidated Appropriations Act, 2022, a massive omnibus appropriations package, which President Biden signed into law on March 15, 2022.

[2] Statement by President Biden on the Introduction of the Violence Against Women Act Reauthorization Act of 2022, February 9, 2022, available at https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/statements-releases/2022/02/09/statement-by-president-biden-on-the-introduction-of-the-violence-against-women-act-reauthorization-act-of-2022/.