The death of a yet another indigenous Maya child from Guatemala while in the custody of U.S. Customs and Border Protection demands that the United States adjust its approach and end its inhumane and cruel immigration policies and practices -- giving special attention to the care and treatment of children seeking asylum at the border. Seven-year-old Jakelin Amei Rosmery Caal Maquin, a Q’eqchi’ Maya girl, died on December 8 in a Texas hospital. Felipe Gomez Alonso was from the Maya Chuj Nation; the eight-year-old died on Christmas Eve.

These tragedies also demand that the United States, international agencies, and humanitarian and human rights organizations take a hard look at the ongoing political repression, lawlessness, and the discriminatory legal system in Guatemala – fostered by decades of foreign aid and investments – that force the migration of indigenous peoples to the U.S. and fuel violence and other terrible human rights violations against those who stay home.

The UN World Food Program says “the face of Guatemalan hunger is young, female, indigenous and rural.” Seven-year-old Jakelin Caal Maquin embodies that description. It’s been reported that Jackelin’s father, a subsistence farmer with a plot of land too small to support a family, went to the United States in search of work. He took Jackelin with him – perhaps because he had heard that his chances of staying in the United States were better if he arrived with a child.

For the Maya and other indigenous peoples in Guatemala, land rights are not only a foothold on opportunity, their lands and resources are fundamental to their physical and cultural survival. But decades of U.S. policy supporting repressive Guatemalan regimes helped spark a 36-year civil war that resulted in the displacement and slaughter of hundreds of thousands Maya and other indigenous peoples.

It has been 28 years since the signing of the Guatemala Peace Accords, which promised to return land to the indigenous peoples from whom it was stolen centuries earlier. But indigenous peoples are still struggling for their land rights. Today, lands remain concentrated in the hands of a few. For example, just five companies own all the palm oil plantations in the country – including those north of San Antonio de Cortez, where Jackelin’s father is reported to have sought employment. These plantations occupy an area of land equal to that used by more than 60,000 subsistence farmers. The Maya people are the majority population in Guatemala, consisting of 22 different indigenous nations; but the political and social landscape of the country is governed by a minority, a de facto apartheid in the Americas.

Indigenous peoples’ rights of self-determination over their territories, environments, and natural resources have little protection under Guatemala’s legal framework, creating extreme insecurity and vulnerability for indigenous peoples. The lack of legal security is driving land grabs, evictions, violence, and environmental damage because of mining, palm oil production and other agro-industries, hydroelectric dams and logging. As of October 31, 20 human rights and indigenous rights defenders had been murdered in 2018, making the country among the most dangerous in the Americas.

The Indian Law Resource Center is advocating for more humane policies at the U.S. border and also working to advance the rule of law and indigenous land rights in Guatemala. Our work to help the Maya Q’eqchi’ community of Agua Caliente secure legal title to their lands and resources could set an important and profound legal precedent for Guatemala’s indigenous majority.

As 2018 comes to a sad close due to the deaths of Jackelin and Felipe, we want to tell you how grateful we are to all of you for your solidarity and partnership in this critical work and for all that you do to support justice for indigenous peoples. Thank you.

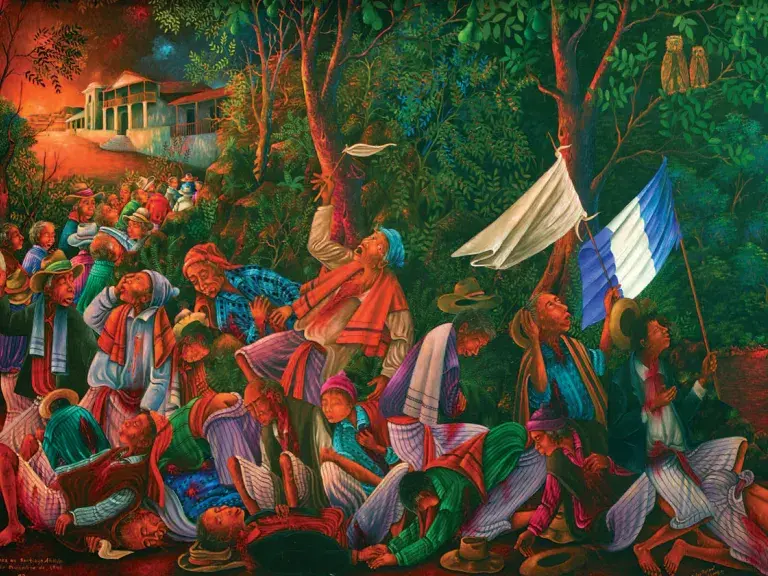

Artwork: Massacre in Santiago Atitlan, by Pedro Rafael González Chavajay